the project

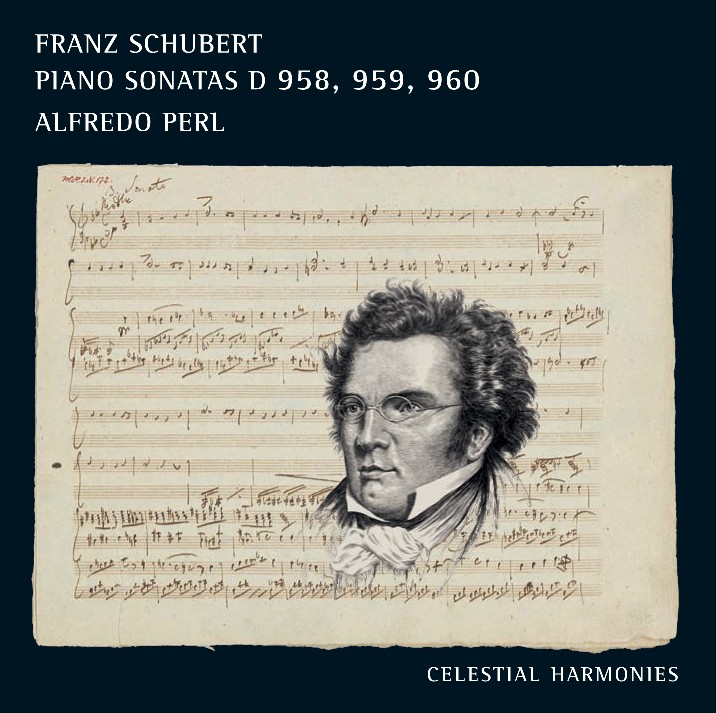

In 1828, Ferdinand Schubert, an older brother of the composer Franz Schubert, had bought an apartment in Vienna's Firmiansgasse, known today as Kettenbrückengasse. The apartment was not ready for his immediate use, as it needed to dry out. This offered an inexpensive - if unhealthy - opportunity to offer temporary accommodation to Franz. It was to prove the last residence for Franz, who had been suffering from a progressive infection since 1824, and was not destined to complete his 32nd year. In the few weeks until his death on November 19th, 1828, he was able to compose, aside from the String Quintet in C and from sketches for a large scale Symphony, three large Piano Sonatas (C Minor, A Major and B Flat Major), which are presented here as recorded by Alfredo Perl.

In the course of his struggle with this genre, so dominated by Beethoven, Schubert had already begun 18 sonatas, and left nine incomplete. For many years, Schubert's instrumental works were regarded as inferior to his vocal music, perhaps due to the ever present lyricism in his music. These three Sonatas were only published eleven years after his passing away - in 1839 - by A. Diabelli & Co. Nevertheless, they offer a rich variety of purely instrumental structures. The earlier Sonatas already contain some real jewels - Schubert could even be an extrovert innovator, as the Wanderer Fantasy proves. Although Schubert was never quite the ever progressive inventor, his highly imaginative and creative ideas realigned the piano sonata to his own form of expression and gave it new life alongside and after Beethoven.

It is unclear whether the astonishingly fast composition of these Sonatas was due to an expectation on Schubert's part of more commissions, or whether it was a symptom of a last surge of creative energy before his terminal decline.

The inner journeys of these Sonatas reveal infinite expanses. Externally, all three follow the classical tradition closely. However, each one fills this form with an irrepressible wealth of musical inspiration and retraces the full path of Schubert's development as a composer. The source from which he now drew his inspiration had become a never-ending source.

As recently as in the 1970s, Alfred Brendel noted a lack of respect

for Schubert's instrumental works. The general improvement of this

is probably not least a result of his efforts. Perhaps it is also

a result of a widespread desire for a return to music which reflects

time and touches the soul, rather than the ever-present and undesired

functional noise that it is today.

the artist

For 25 years now Alfredo Perl has been one of the most influential performers in the field of classical and romantic piano music. His concert career was launched in Germany and England in the 1980s, and since then has taken him across the world. His repertoire, founded on Beethoven's 32 Sonatas, is still centred on these today. Listeners at his first concert in Germany - at the Cologne Musikhochschule in 1984 - were struck by a strong characteristic of his rendition of Beethoven's Sonata Les Adieux Op. 81a: this pianist, born in Santiago de Chile in 1965, impressed not principally through strength and virtuosity, but through conviction and persuasive elegance. In 2007, Alfredo Perl was named Professor for piano at the Detmold Music Academy.

Anyone taking the opportunity to hear Alfredo Perl in concert should hear him not only as a soloist, but also in the realm of chamber music and concerto appearances. Soon after concluding his studies with Günter Ludwig in Cologne and Maria Curcio in London he performed the cycle of Beethoven's 32 Sonatas at several venues, including London's Wigmore Hall, the high temple of British piano culture.

When radio producers at classical music stations wish to play recordings of Beethoven Sonatas, they often select the recordings made by Perl at that time. Why might this be?

It is characteristic of Perl's playing that, compared to other leading pianists he has no marketable mannerisms such as a typical non-legato touch or a fondness for unmotivated accents. Neither does he belong to those less original imitators of Glenn Gould who like to demonstrate their analytic intelligence. Perl's attitude is a different one. Interpretation is a synthetic process resulting from continuous reflection on the work. It must satisfy the highest æsthetic demands. In this respect, Perl is not a revolutionary, but an heir to a classic European piano tradition.

Perl's style is refreshingly, almost excitingly, free of mannerisms. It focuses the attention of the listener wholly on the music. He wishes to express something about the music, not through it. Music is not the medium, it is the destination, the focus. Perl is a pianist one listens to, as opposed to listening for. His musical identity develops from the music itself, a result of the never-ending, even hermeneutic, cycle of reflection, comprehension and realization of substantial and complex works of art. For this reason he is particularly successful in the large-scale, demanding works of the repertoire, the Diabelli Variations, the Hammerklavier Sonata, the diffi cult Op. 101, the last three Schubert Sonatas or the great works of Liszt's Weimar years. The occupation with smaller works is often a fertile by-product of this.

The characteristics of Perl's playing always form a clear and beautiful style that is readily identifiable. Those familiar with his playing will easily recognize his recordings on the radio, should they miss the announcement. His timing is particularly unique. Perl takes care to control even the smallest nuances of time in the course of each episode, making each little melody a whole in itself. "If you wish to enjoy the whole, you must see the whole in every part", wrote Goethe or Schiller in their jointly compiled collections of epigrams, Xenien. With this in mind, Perl organizes the parts of a work and fuses them into an organic whole. In music, all proportions have to be organized in time, at once showing the similarity and the difference between music and architecture. As German critic Joachim Kaiser once said about Colin Davis, and as could equally be said of Perl, "He is a master of hearing structure". Perl does not attempt to reveal structures - he realizes them and makes them tangible.

These recordings therefore belong to a different world than some others one may come across - whether it be those competing with the sluggishness of their tempi, portrayals à la mode of the prematurely wise genius and his inner suffering, or those that misunderstand the nature of the music entirely and seek only the brilliance of the surface.

In Perl's playing one can recognize the greatness, maturity and depth of a multi-faceted personality. The works here are clearly related to their great siblings from the chamber works of Schubert's last years: the String Quintet, the late Quartets and the two Piano Trios. Perl's approach is unmistakably metainstrumental.

Nevertheless, Perl also remembers that great music always tries to

seduce the listener, a vital part of its greatness. He manages to

combine depth and seriousness with charm and elegance in a unique

manner. It is as if his aim were to show that music is no inhuman

skill to be only admired, but that it is a fundamental human necessity,

vital to our lives. In the case of Alfredo Perl one does not ask about

correctness or incorrectness, nor about good or bad, least of all

about likes and dislikes. Great performers speak to us, and we to

them, about things on a different plane, such as the nature and substance

of the music.

discography

tracklist

| CD 1 | ||

| Piano Sonata D 958 in C minor | 30'24" | |

| 1 | Allegro | 10'06" |

| 2 | Adagio | 8'34" |

| 3 | Menuetto. Allegro | 3'14" |

| 4 | Allegro | 8'29" |

| Piano Sonata D 959 in A major | 38'47" | |

| 5 | Allegro | 12'29" |

| 6 | Andantino | 7'50" |

| 7 | Scherzo. Allegro vivace | 5'15" |

| 8 | Rondo. Allegretto | 13'11" |

| Total Time: | 69'21" | |

| CD 2 | ||

| Piano Sonata D 960 in B flat major | 44'31" | |

| 1 | Molto moderato | 21'47" |

| 2 | Andante sostenuto | 9'57" |

| 3 | Scherzo. Allegro vivace con delicatezza | 4'01" |

| 4 | Allegro ma non troppo | 8'44" |

| Total Time | 44'31" |