Overlooked No More: Robert Johnson, Blues Man Whose Life Was a Riddle

Johnson gained little notice in his life, but his songs — quoted by the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton and Led Zeppelin — helped ignite rock 'n' roll

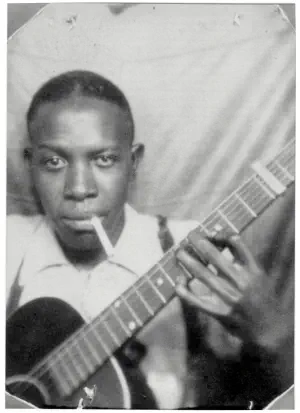

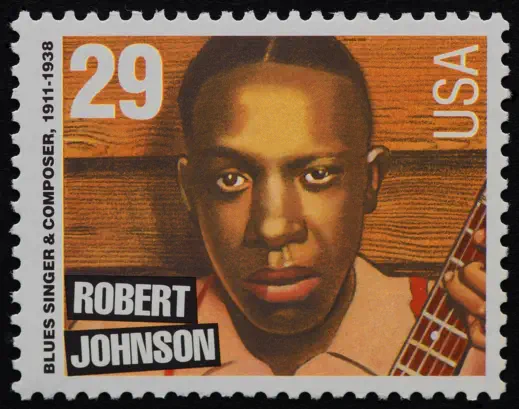

A photo booth portrait of the blues musician Robert Johnson. It was taken around 1930 and is one of three confirmed photographs of him; the cigarette was removed from the picture for the postage stamp in 1994

September 25, 2019

By Reggie Ugwu, The New York Times

Little about the life Robert Leroy Johnson lived in his brief 27 years, from approximately May 1911 until he died mysteriously in 1938, was documented. A birth certificate, if he had one, has never been found.

What is known can be summarized on a postcard: He is thought to have been born out of wedlock in May 1911 in Mississippi and raised there. School and census records indicated he lived for stretches in Tennessee

and Arkansas. He took up guitar at a young age and became a traveling musician, eventually glimpsing the bustle of New York City. But he died in Mississippi, with just over two dozen little-noticed recorded songs to

his name.

And yet, in the late 20th century, the advent of rock ’n’ roll would turn Johnson into a figure of legend. Decades after his death, he became one of the most famous guitarists who had ever lived, hailed as a lost

prophet who, the dubious story goes, sold his soul to the devil and epitomized Mississippi Delta blues in the bargain.

In the late 1960s, the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton/Cream and Led Zeppelin covered or adapted Johnson’s songs in tribute. Bob Dylan, who, in the memoir “Chronicles: Volume One”, attributed “hundreds of

lines” of his songwriting to Johnson’s influence, included a Johnson album as one of the items on the cover of “Bringing It All Back Home”.

In the 1990s, a lightning-in-a-bottle compilation of Johnson’s music — “The Complete Recordings”, released by Columbia Records in 1991 — revived interest in the blues for yet another generation, selling more

than two million copies and winning a Grammy for best historical album. In 1994, a United States postage stamp in Johnson’s likeness memorialized him as a national hero.

The chasm between the man Johnson was and the myth he became — between mortal reach and posthumous grip — has marooned historians and conscientious listeners for more than a half-century. It would

have made fertile terrain for one of Johnson’s own songs, many of which frankly and masterfully tilled the everyday hopelessness and implausibility of segregated African-American life.

Indeed, his story is no more or less than the handiwork of the country in which it was written; a country where the legacy of African-Americans has often been shaped by others.

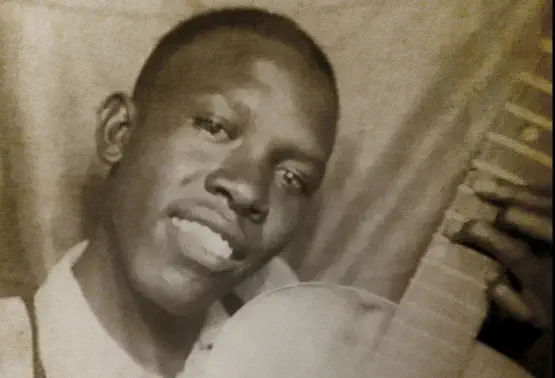

The second of three confirmed photographs of Robert Johnson

Johnson was born in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, in the wake of the Redemption era, a period following Reconstruction when white supremacists across the South reversed many of the freedoms and rights granted blacks

after the Civil War.

His mother was Julia Major Dodds, the daughter of slaves, who had 10 children with her husband, Charles Dodds, before conceiving another with a field hand named Noah Johnson.

When Robert was around 7, his mother married another man, and he moved with her to Robinsonville, Miss. It was there, in the town’s popular juke joints — segregated stores or private houses that doubled, after

hours, as recreational places — that his now legendary music career began.

As recounted in Barry Lee Pearson and Bill McCulloch’s biography, “Robert Johnson: Lost and Found” (2003), Johnson, perhaps as a teenager, attended juke joint performances by the early Delta blues pioneer

Son House. The young musician had trained on a diddley bow — one or more strings nailed taut to the side of a barn — and wasn’t much of a guitar player. But a surplus of ambition outweighed his lack of skill.

In a 1965 interview with the writer and academic Julius Lester, cited by Pearson and McCulloch, House recalled Johnson’s habit of commandeering the stage during intermissions in order to play songs of his

own. Chastened by House — and the howls of his audience — Johnson reportedly left town. But he returned six months later eager to perform again, this time asking for House’s permission.

“He was so good!” House said of the new and improved playing style Johnson exhibited on the night of his re-emergence. “When he finished all our mouths were standing open. I said, ‘Well, ain’t that fast! He’s

gone now!’ ”

Variations on House’s story — a mysterious sojourn, sudden virtuosity — are the source of the myth that Johnson, like Faust, sold his soul in exchange for his genius.

But friends of Johnson have given conflicting testimonies as to whether the singer himself ever endorsed the tale. And the two of his songs most often associated with the story, “Cross Road Blues” (recorded as

“Crossroads” by Cream) and “Hellhound on My Trail,” make no mention of an unholy encounter. Historians now suggest that Johnson’s real benefactor may have been a guitarist in the Hazlehurst area named Ike

Zinnerman (sometimes spelled Zimmerman).

As Johnson’s music began to find an audience in the years after his death, however, critics — many of them white and mystified by black culture in the South — leaned into the legend.

As the music historian Elijah Wald wrote in “Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues” (2004): “As white urbanites discovered the ‘race records’ of the 1920s and ’30s, they reshaped

the music to fit their own tastes and desires, creating a rich mythology that often bears little resemblance to the reality of the musicians they admired.”

What is true is that the guitar playing on Johnson’s recordings was unusually complex for its time. Most early Delta blues musicians played simple guitar figures that harmonized with their voices. But Johnson,

imitating the boogie-woogie style of piano playing, used his guitar to play rhythm, bass and slide simultaneously, all while singing.

Another innovation associated with Johnson, as noted by the critic Tony Scherman in 2009 in The New York Times, is the walking bass. Appearing on the Johnson songs “Ramblin’ on My Mind” and “(I Believe I’ll) Dust

My Broom,” the walking bass — a low, ambling rhythm that evokes a swaggering strut — became a building block of both Chicago blues and rock ’n’ roll in the hands of the Johnson apostles Muddy Waters and Elmore

James.

Like many blues men who lived in the shadow of Jim Crow, Johnson was a wanderer for most of his adult life and performed in juke joints — often traveling with his fellow blues artist Johnny Shines — as far as

New York City. He married twice — first to Virginia Travis, who died while giving birth to their child, who also died; then to Caletta Craft. In 2000, a court ruled that Claud Johnson, the child of a girlfriend of Johnson’s

named Virgie Jane Smith, was legally his son.

What survives of Johnson’s short career is based on his only two recording sessions, arranged by the American Record Company executive Don Law in 1936 and 1937 in Texas. One song from the first session,

the vibrant “Terraplane Blues,” sold a respectable 5,000 copies, giving the singer the only real taste of fame he would know in his life.

Another record executive, John Hammond of Columbia Records, championed Johnson’s music decades after his death. Hammond, who launched the recording careers of Billie Holiday, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan and

Bruce Springsteen, issued a posthumous album in 1961, “King of the Delta Blues Singers”, which compiled most of the American Record Company recordings.

The album captivated a fledgling generation of musicians at the dawn of rock’s golden age. As Eric Clapton wrote in 2007 in “Clapton: The Autobiography”, describing his first encounter with “King of the Delta

Blues”, “I realized that, on some level, I had found the master.”

The story of how Johnson died, like so many facts of his life, is contested.

A death certificate recovered by the researcher Gayle Dean Wardlow showed that he died on Aug. 16, 1938, at a plantation near Greenwood, Miss. The cause was complications of syphilis, according to a note

on the back of the certificate that was attributed to the plantation’s owner.

But David Honeyboy Edwards, a contemporary of Johnson’s who is believed to have performed with him just days before his death, said that Johnson had been poisoned, and that he was probably targeted by

the vengeful husband of one of his mistresses.

The location of Johnson’s grave has never been confirmed. Headstones at three different churches in the Greenwood area claim to mark his resting place — the final riddle of a man whose brief, turbulent life

became a cipher nearly as sensational as his songs.

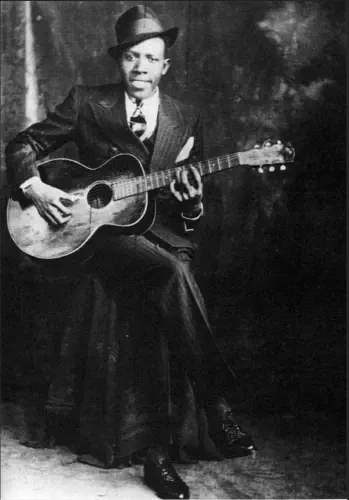

The third picture to have survived, presumably taken in the same photo booth as the one above

B

L

ACK O SUN

Originally, the British musicians assumed, for better or

worse, that Johnson’s works were not under copyright;

they were usually treated as “traditional” works which

could be arranged by anyone who could then claim a new

copyright for their adaptations.

Coming from John Mayall’s school of British blues, the

guitarist Jon Mark, later known as leader of the band

Mark-Almond, was the first who — in 1972 — admiringly

titled his production “In Memory of Robert Johnson”.

Among others, Spencer Davis and Alun Davies were

playing; singer Paul Williams, then with a band called

Juicy Lucy, did the vocals. This release was the first

record to celebrate Johnson’s music; Nigel Thomas who

was Joe Cocker’s manager at the time acted as co-

producer. The Lp first appeared on Nashvillle’s famed

label King Records. Tucson, Arizona-based Black Sun

Music re-issued the record in 1992 after the original

label had gone under (

Black Sun 15017-2

).

p.o. box 30122 tucson, arizona 85751

+1 520 326 4400 +1 520 326 3333 fax